A few weeks ago, I was faced with the challenge of re-implementing a file-upload gateway. The top-level steps it needed to accomplish were the following:

- Receive metadata and process it

- Receive and pass on a binary blob to a third party without caching to disk

- Notify another service about the completed process

But there is a twist: Step 2 might need to happen before Step 1.

This depends on the ordering of the data during the upload, which is not controllable by the application. If the blob is received first, it also needs to be passed on immediately, since caching to disk is not allowed and caching in memory would quickly kill the application if more than a handful of uploads were to happen simultaneously.

No matter the order of the first two steps, both their results are required as inputs for step 3.

Now, how does one design an interface with multiple methods, ensuring they are only called in a certain set of sequences?

The Unsafe Solution

The simplest idea is to just create an interface with three methods and define the rules for calling them in a docstring.

interface Gateway {

/**

* Call this method first or after uploadBlob(InputStream)

*/

void provideMetadata(Metadata data);

/**

* Call this method first or after provideMetadata(InputStream)

*/

void uploadBlob(InputStream blob);

/**

* Call this method last

*/

void notify();

}

That's fine if you are the only one ever touching this code and you diligently read your own comments. But as soon as other developers come into play, you should think a bit more defensively, and this design is not really safe.

Imagine another developer interacting with this interface via autocomplete in their IDE. They see the three methods, nothing more. You'd need to pray that they are curious enough to read the docstrings diligently and to adhere to your written rules.

Getting Into Order

Enforcing the ordering of methods is not easy. There is the strategy of "chaining by signature" (or at least that's how I call it). Simply put, you return the intermediate result of interface method A and make it a required parameter of interface method B.

class CachedMetadata {}

class UploadedBlob {}

interface Gateway {

CachedMetadata provideMetadata(Metadata data);

UploadedBlob uploadBlob(InputStream blob);

void notify(CachedMetadata meta, UploadedBlob blob);

}

If there is no way for the caller to instantiate this intermediate result type by themselves, the interface methods will only be callable in the order supported by their input and output types.

Still, this is a bit hacky, and as mentioned, it only works in statically typed languages with access modifiers (sorry Python). One might also argue that this is a somewhat leaky abstraction since the caller is now required to carry the intermediate result over to the next method.

Even weirder is the case where there is actually no data to transfer between these objects.

Revealing Just Enough

This is where I had the idea of adapting the latter idea by simply returning the next method to call as a closure. This solves the main issues of the two previous designs:

First, there is no trial-and-error required to find out which method of the interface to call next: it is immediately available as the result of its predecessor method.

Second, no internals are leaked to the caller and every intermediate result is stored in the closure. This also works in languages like Python!

Consequently, I went and implemented the gateway using this design.

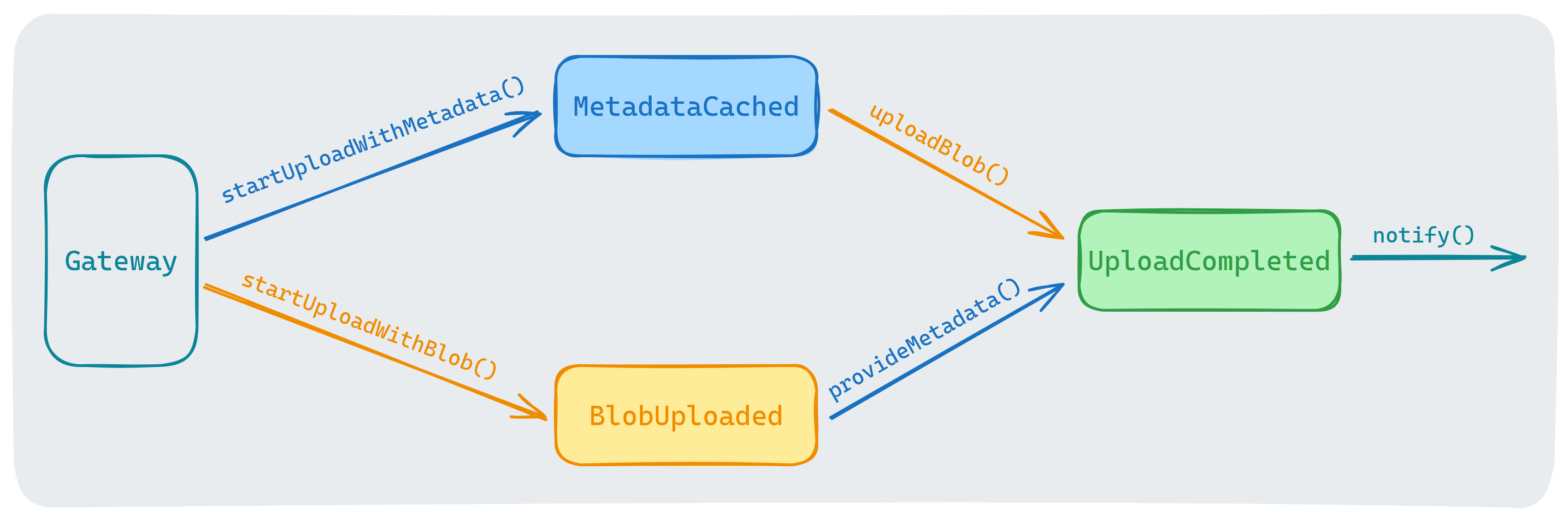

interface Gateway {

MetadataCached startUploadWithMetadata(Metadata data);

BlobUploaded startUploadWithBlob(InputStream blob);

}

interface MetadataCached {

CompletedUpload uploadBlob(InputStream blob);

}

interface BlobUploaded {

CompletedUpload provideMetadata(Metadata data);

}

interface UploadCompleted {

void notify();

}

This results in a kind of type-graph that leads the caller from start to finish:

Naming Things

After I was done implementing, I decided to write this post and started to think about a possible title. That's when I asked good ol' ChatGPT whether there already was a name for this pattern I came up with.

And surely there was! So I learned that it is called the Step Builder (I was also a bit prout at the same time to have come up with this without knowing about this pattern).

Of course, not all is gold. Most obviously, representing every intermediate step in every permutation of step sequences yields an exponential number of required types. While this pathological case may not always occur and may be reduced through simplifications, it puts a limit on which use cases may be reasonably covered by this pattern.

FP With Extra Steps

And, lastly, if you have experience in functional programming, this might be you:

And you are right, the step builder pattern is somewhat related to currying!

If you have not heard of this concept, you can read more about it here. The gist of it is the capability of applying functions partially (with a subset of parameters). This partial application returns a new function with the remaining parameters as an input and the same output as the original one.

But while functional languages oftentimes provide this as a built-in feature (e.g., Haskell or Scala), the step builder pattern can implement partial application in any language with a concept of functions as return types.

Of course, there are more differences between both patterns, but I do not aspire to enter that holy war.

In summary, I enjoyed implementing the functionality of the upload gateway in this style, and the interface is nice and concise and represents the exact way the procedure is meant to be called.

Have a nice day!

Chris